At the end of the 1950s and at the beginning of the 1960s, in Europe and elsewhere in the world, several sculpture symposia were founded. The initiatives, for the most part, came from the artists themselves. According to Janez Lenassi, one of the creators of the international Forma viva in Slovenia, they ‘emerged as a reaction to the conditions in culture, which diverged from the declared aims of development and conformed to the practice of everyday life’. Artists, especially sculptors, experienced the political and economic (that is, consumerist) mentality of the hyper-productive way of life – which, in plastic arts, contented itself with soulless solutions in the spirit of ‘modernist design’ – as a threat to the freedom of artistic creation. They resisted the anonymous production of artefacts for the broadest possible market, for they did not want to transform their studios into assembly-line production halls. They turned to classic sculptural materials. They tried to be attentive to the laws of the material and to work in the ideal conditions of sustainable attendance to the primary expressions of the environment and in the limitless extensions and dimensions.

All these principles were interwoven into the idea of the first international Forma viva sculpture symposia in Slovenia at the beginning of the 1960s, and they remained – with greater or lesser success – the guideline of all subsequent meetings until the end of the 1980s, when this important international artistic manifestation, for various reasons, came to a halt, at least temporarily, in the majority of its traditional locations.

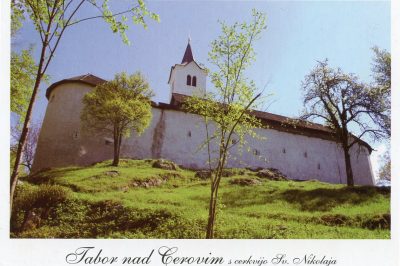

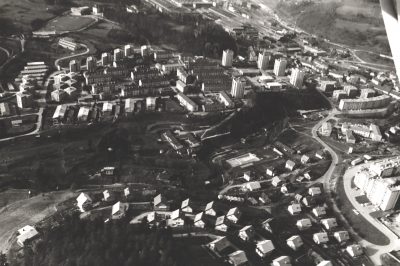

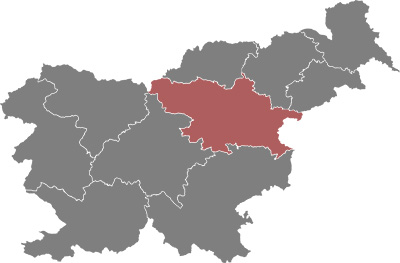

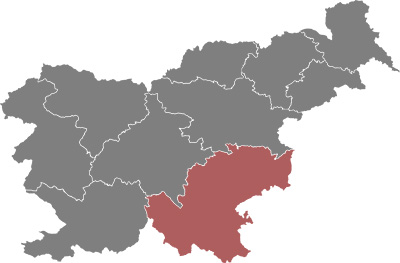

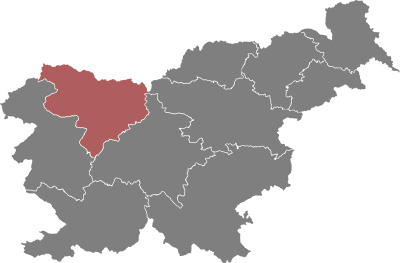

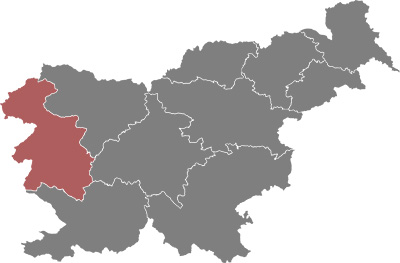

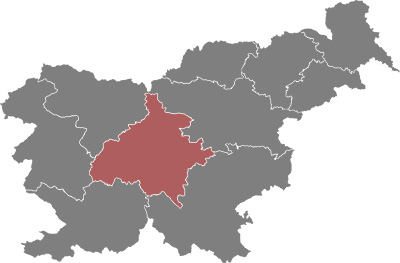

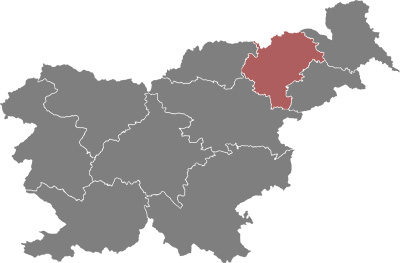

It started in 1961 with sculpting wood in Kostanjevica and carving stone in Portorož. Only three years later, Forma viva in the ironworks town of Ravne joined these already established artistic centres, which managed to express organically the cultural and landscape heritage of their ambients. Namely, the year of 1964 was the time when the production in the renovated and expanded ironworks in the middle of the Mežiška valley was in full bloom, and together with it the town was developing, too. High-quality steel was the symbolic material of the industrial age; therefore, it is no coincidence that the idea – which was brought to Ravne by Franc Fale, later on a long-time director of the ironworks, after an accidental meeting with the representatives of Forma viva in Ljubljana – was received so well. However, while the monumental sculptures in Kostanjevica and Portorož provided constant enrichment to the galleries of sculptures in the enclosed locations in the vicinity of the picturesque Cistercian monastery and on a strip of seashore in Seča, the idea in Ravne was different. In the sixties, the town experienced intense construction of new residential areas, hence, the sculptors, as a rule, created their works for predetermined urban ambients. At first amidst the apartment blocks in the workers’ area in Čečovje, and later on at exposed points in the wider urban district. The original idea even envisaged the installation of sculptures in well-chosen locations where, as unique artistic attractions and veduta-like emphases, they would function as spatial coordinates of sorts, determining the starting points for town planning. However, this extraordinary idea was never fully accomplished. Truth be told, we should even admit that, with the changes in the individual enclosed ambients of the urban tissue, the conditions for compelling artistic effects gradually deteriorated even for some of the sculptures that had been integrated congenially into their environment at the time of their creation and installation.

Despite their markedly abstract artistic expression, the thirty sculptures created by just as many artists – seven Slovenians, five Japanese, three Englishmen, two Germans, two Croatians, two Italians, two Americans and a Yugoslavian, a Macedonian, an Austrian, an Irishman and a Canadian – at seven symposia between 1964 and 1989 integrated into the visual image of the centre of the valley by the Meža river to such an extent that they became its inextricable element and a symbolic expression of the local ironworks tradition, which is more than three hundred years old. Even though in Ravne, a provincial industrial environment, the idea of an artistic symposium had been met all along with very different, even conflicting responses, the locals nevertheless accepted the unusual ‘living forms’ made of steel. Many have grown used to them to such an extent that they do not even notice them anymore, but nobody has been left completely indifferent, as evidenced by some more or less humorous and witty names invented by locals for specific sculptures. Thus, Tihec’s work in Čečovje has been named a ‘monstrance’, Hoskin’s an ‘aeroplane’, Basaldella’s sculpture reminds people of a radar, Yoshikawa’s in Janeče is reminiscent of a snail, while Trudeau’s sculpture next to the fire station is said to resemble a beheaded human figure, which represents the bureaucratic mentality of the factory leadership. The mission of art has never been merely in its aesthetic, decorative function, but also in its intriguing provocativeness. On the whole, it was certain individuals who contributed most to the successful actions of Forma viva in Ravne, which developed into an extremely important traditional manifestation in the twenty-five years of its existence; the realisation of this demanding international project would not have been possible without these individuals. There is a whole series of meritorious people that should be mentioned here; in addition to the initiator Fale, at least one other name should be singled out among the organisers, namely the factory’s cultural animator Franc Boštjan; but above all, there are all those master assistants in the ironworks, who provided comprehensive technical assistance to the artists and without whom these immense sculptures made of steel could not have come into existence. In those years, when the ironworkers in Ravne boasted about the thousands of tons of produced steel, the occasional summer ‘circus’ with diligent, but extravagant and capricious artists was, no doubt, viewed upon with ironic derision among the workers and the greater part of the local population, but one could also detect self-assured vanity, which manifested itself in the exceptional hospitality shown to the visiting sculptors and in professional collaboration. Every time, the workshop set up in a secluded corner of one of the courtyards in the gigantic factory complex gave the impression of a lively fair, smiled at benevolently by the passers-by, who entertained no harmful, but also no particularly favourable thoughts with regard to the happening, and a moment later they were already immersed in more ‘serious’ thoughts.

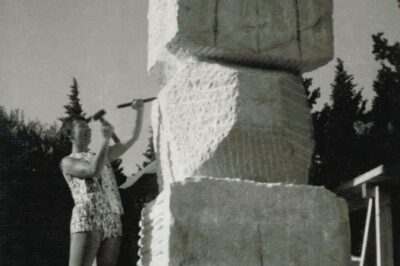

The first edition of Forma viva in August and September 1964 was conceived as a one-off event. They intended to use the works created by seven sculptors to enliven the new residential area in Čečovje, where they started arranging the greens, gardens and parks. But the space between the ironworks and the school of metallurgy, which was earmarked for a worksite, was enlivened already at the beginning of summer, when, ahead of all others, Canadian artist Yves Trudeau arrived in Ravne, created his sculpture – an effectively modernist composition with a distinctive lift in height – and returned to his homeland before the official launch of the symposium. In the friendly and intensive work atmosphere, the six remaining participants – independently, but within a creative collectivity that is typical of symposia – brought to fruition their monumental ideas: Zoran Petrovič, already a recognised artist, welded stainless steel for the very first time; the informalist texture of scraps of steel plates attracted Stevan Luketić; Japanese artist Oda designed a suggestive ‘living form’ for a well thought out location, which, however, was totally spoiled later on by unsuitable buildings; Slavko Tihec conceived his ‘traffic lights’ as a mobile structure revolving around its own axis, while Giancarlo Marchese, who went on to become a famous professor at the Brera Academy in Milan, kept the crystalline form of his design within the confines of a more intimate format.

The success of the first symposium encouraged the organisers to invite four new artists to contribute their creative works the following year; this time around, there were no participants from Slovenia or Yugoslavia. The famous Dino Basaldella came from the nearby Friuli and, using a few centimetres thick steel plates, constructed an expressive sculpture, which dominates the old part of the town from the edge of the Čečovje terrace. From St Martin’s School of Art, the young Portuguese artist Waldemar D’Orey brought the idea of pure and playful modernist exploration in the spirit of geometrical art and op art, while even the master assistants at the ironworks worksite were amazed by the masters of welding, Hoskin from England and Yoshiba from Japan, and their incredible metier skill in shaping metal.

In 1970, after a slightly longer intermission, four sculptors worked on Forma viva again. Katsuyi Kishida came to Ravne thanks to the solid collaboration with an art association in Japan; his effective minimalist sculpture was first installed in Dobja vas, in front of the ironworks administration building, and later on reinstalled at the entrance to the new residential area in Javornik. Barna Sartory, Austrian artist of Hungarian origin living Berlin, who travelled the world in the spirit of his cosmopolitanism and who was commissioned to carry out several projects in the US, gave an emphatically constructivist note to the expanded field of his creativity, committed equally to sculpture as well as to architectural planning. Ernst Eisenmayer, too, established himself as an Austrian émigré in Great Britain after the Second World War. His spatially illusionist sculpture, made of steel cross-sections and standing by the road through the main square in Prevalje, attracts and intrigues the attention of passers-by. And in front of the hotel in Črna, there is a characteristic sculptural accomplishment created by France Rotar, the leading Slovenian creator of metal statues. A year after its creation, Rotar was awarded an important Slovenian state award, the Prešeren Fund award, for this large ball with an open centre.

Five years later (which became the established temporal rhythm of symposia in Ravne), in 1975, three new artists engaged with steel and iron. Another Japanese artist was part of this company from different parts of the world: Yuki Oyanagi created a figural composition (the only one among all projects of Forma viva in Ravne!), which is on display on the platform in front of the Tuš supermarket in the centre of the town. Apart from the slanting pillar penetrating the sky in Mežica, Petar Hadži Boškov, the founder of modernist sculpture in Macedonia, created the liberation monument in Ravne a few years later. Danish artist Sörensen was an old acquaintance from sculpture symposia in various towns of the former Yugoslavia; his unusual sculpture in Javornik reveals the topical sentiment of art at the time, which, in painting, resonated in the so called New Image.

For the very first time, two women artists participated in the fifth symposium in 1981. Milena Braniselj used to opportunity to create monumental works and accomplished a spinning form of imposing dimensions – a mobile, which constitutes the central emphasis of her sculptural work in general. And German artist Irmtraud Ohme, professor at the academy in Halle, brought to fruition the unconventional idea of a tripartite, spatially developed and vividly coloured sculpture. American artist Tom Lindsey, who also works in the field of ecological, solar architecture, used found semi-finished products from the ironworks imaginatively to construct a futurist imaginary machine in front of the grammar school in Ravne. Initially, the light and transparent ‘living form’ by Croatian sculptor Zvonimir Kamenar from Rijeka replaced the relocated sculpture by Kishida in Dobja vas, only to be itself moved to a new location in the middle of the town’s central roundabout between the Eastern entrance to the ironworks, the bus station and the municipal building.

For the first time, the symposium in 1984 presented the participating artists with a theme – Peace: No more war – for their activities were tied in with the following year’s celebrations commemorating the fortieth anniversary of the last fights of the Second World War in Poljana. Only the monumental and symbolically profound statue by the insightful American landscape artist Gary Dwyer was installed in the future memorial park at the site of the final battle, while the less thematically tuned in sculptures by Robert Stell, who, as a young sculptor straight out of the academy, seized the opportunity with a great level of maturity, the seasoned master Dušan Tršar and the Irishman Jim Buckley were put on display in the park in front of the hotel at Rimski vrelec near Kotlje, in the green area next to the municipal building in Ravne, and in front of the primary school in Prevalje.

The last Forma viva symposium in the first period before the intermission was organised in 1989, when the first signs of global crisis in heavy industry were already becoming apparent, and Ravne was, of course, no exception. In the conditions, which were seemingly not comparable to those of the ‘golden’ sixties, Matjaž Počivavšek created a marvellous sculpture: he forged it with the assistance of local masters and using monumental steel ingots. The statue, weighing more than ten tons and standing in the centre of a large green area amidst the apartment blocks in Javornik, explores sculptural space with sensibility, surprising ease and minimalist precision. German artist Peter Kärst also brought his idea to fruition in the vicinity, while sculptress Rene Rusjan (who came to the symposium very late, as a last-minute replacement for an Israeli artist who had cancelled his participation) prepared, for the first time in the history of the Ravne symposium, a spatial sculptural installation designed for the interior of the new post office building. The organic structure created by the Japanese Ishikawa in the suburban neighbourhood of Janeče, close to the home of the ‘father’ of Forma viva in Ravne, France Fale, rounded off the yields of the quarter of the century and, with its postmodernist address, indicated the time of decline of heroic modernism of the industrial age.

Afterwards, the circumstances, which made possible the ideal conditions for artistic creativity in the preceding decades, changed radically. Post-industrial reality rocked the foundations of the economic prospects of gigantic, oversized production complexes – not only in Slovenia, but also elsewhere in the world – and it changed, to a large extent, the way of thinking despite the long tradition and the proverbial patience and stubbornness of the people from the Koroška region. New contents and new possibilities were being sought, while they tried to preserve predominantly those existing creations whose value had already been affirmed. When considering the possibilities of cultural tourism in the region, the Forma viva sculpture gallery became one of their trump cards. Hence, the local communities in the Mežiška valley entrusted the Carinthian Regional Museum (Koroški pokrajinski muzej) with preserving the legacy of Forma viva in Ravne. On the occasion of the 35th anniversary of the symposium, in 1999, the museum made the first step towards evaluating this important part of the national visual arts heritage by organising two exhibitions, in Ravne and in Ljubljana, and soon after it also secured expert preservation of the existing collection of thirty steel sculptures installed in the urban spaces of the towns in the Mežiška valley.

The local community, too, has been aware all along of the significance of this first-class international collection; with the support of the municipality of Ravne na Koroškem and some successful companies, which emerged from the ‘ruins’ of the once mighty ironworks, the museum tried to revive the meeting of sculptors and so, after nineteen years, in 2008, they organised another symposium, to which the expert committee invited Italian artist Graziano Pompili and Slovenian artists Roman Makše, Boštjan Drinovec and Primož Oberžan. The first three had already worked at other Slovenian worksites, where they had made a strong impression; hence, their achievements in Ravne were also executed in the direction of searching for new possibilities of using diverse steel or metal materials. Roman Makše’s monumental composition titled From Here to Here (Od tod do tod), which has become part of the design of the new central square in the residential area in Čečovje, opens up – again, for the artist has already done this in the work created on the occasion of the revival of the symposium in Kostanjevica – the field of the status of sculptural mechanism, this time around through a provocative combination of various metal materials. The Sonic Cloud (Sonični oblak), created by Boštjan Drinovec and Primož Oberžan, which is installed in front of the administration building of the company Sistemska tehnika, is an unconventional sound sculpture made of stainless steel, which reveals totally new dialogical possibilities for monumental sculptures by means of the natural working of wind and accidental visitors, while the schematised archetypal Golden House (Zlata hiša) by Graziano Pompili, whose monumental dimensions are integrated sovereignly into the urban tissue of the town, explores engagingly the issues of public and private.

Even though the companies behind the fence surrounding the once mighty ironworks, particularly Metal Ravne, still take care of the required worksite infrastructure, where artists can create steel sculptures of monumental dimensions, the ruthless present-day logic of market-oriented enterprises has dictated a greater commitment of the local community. The municipality of Ravne has included the Forma viva collection and symposium among the prioritised and strategic projects of cultural development, and it has sensed the identity point in Ravne, which connects the ironworks tradition of several centuries with the present and the future by means of the precious message of artistic creativity. With the successful installation of three new sculptures of contemporary design, created by internationally renowned master sculptors Gorki Žuvela from Croatia, Johannes Vogl from Germany and Slovenian artist Tobias Putrih, who lives in Ljubljana and New York, the last symposium in 2014, which took place within the framework of the promotional project titled ‘Ravne – the Forma viva town’, has given appropriate attention to Forma viva of the Northern leg of the network of four Slovenian worksites, and it has restored its former value.

A comprehensive view of the past and the artistic power and expression of the collection of Forma viva sculptures in Ravne offer many answers in terms of best practice even today, when we are laying new, more fitting foundations for the revival of this visual arts manifestation, which is important not only for the local milieu but, to a great extent, also as a prestigious international event whose great reputation, makes Slovenia recognisable on the European and the world maps of the current visual arts developments. For sculpture may well be the medium of visual arts practice that specifies the status and the properties of numerous forms of contemporary art. While painting, by dint of electronically synthesised image, is becoming increasingly slippery, intangible and transposed into the immaterial iconosphere of virtual worlds, the traditional ‘slowness’ and emphatic ‘physicality’ of sculpture have become an advantage of sorts in the articulation of desires and visions. The seemingly unwieldy, yet, very ‘real’ objects of plastic sculptural design make sure, in their own peculiar way, that the original starting points and the ontology of contemporary art are implemented. Knowing how to take advantage of this specific power of sculpture, the international sculpture symposium Forma viva can compete with similar manifestations abroad. The revived symposium in Ravne has already done an important step in this direction, whereas in future, with its well-considered concept and trusting its noble foundations, it will come alive as an attractive and contemporary international visual arts project.

Marko Košan